The integral formula of Cauchy is so important that we reserve a complete section dedicated to it.

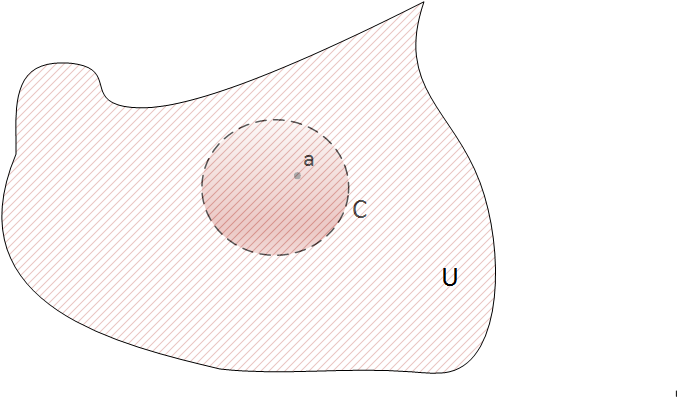

Given f, a holomorphic function in an open set U and given a one point inside of U, then f is holomorphic in a disk surrounding point a.

If C is the boundary of the disk then it is true the following:

$$f(a) =\frac{1}{2\pi i}\ \int_{C} \frac{f(z)}{z-a}dz$$

This very important formula expresses the value of the function at a point inside the disk as function of some values in the boundary of the disk.

Its proof, of which we will see an introduction is based on Cauchy's Theorem for a convex open set:

Proof of the Cauchy integral formula

Because f is holomorphic in all U, lets \(a \in U \). For a we can

\( \lim_{z \mapsto a} \frac{f(z)-f(a)}{z-a} = f'(a)\)

So, it must to exists any \( \epsilon > 0 \) for wich if \( |z-a| < \delta \)

\( \frac{f(z)-f(a)}{z-a} - f'(a) < \epsilon \)

Then function given by

\( g(z)=\left\{\begin{matrix} \frac{f(z)-f(a)}{z-a} & z\ne a\\ f'(a) & z=a \end{matrix}\right. \)

Is continuous in all U and holomorphic in U-{a}.

Its line-integral in every path that surrounds a point is zero since

Theorem3 of section complex integration, then

\( \int_{C} g(z) dz = \int_{D(a, \epsilon)} g(z) dz \)

Because can we take a radius as small as we want and and |g| is continuous into a compact set then it is bounded. Lets M be a bound of g, we have

\( \int_{D(a, \epsilon)} |g(z)| dz \le M 2\pi \epsilon \underset{\epsilon \rightarrow 0}{\rightarrow} 0 \)

We can take for f

\( \int_{C} \frac{f(z)}{z-a} dz = \int_{C} \frac{f(z)-f(a)}{z-a} dz + \int_{C} \frac{f(a)}{z-a} = 0 + 2\pi if(a)\)

What is what we wanted to proof.

The integral formula of Cauchy has important consequences, these are what make the branch of complex variable analysis unique into maths science.

Given f, a holomorphic function in an open set U and given a, one point inside of U, then f has infinite derivatives in a and :

$$f^{(n)}(a) =\frac{n!}{2\pi i}\ \int_{C} \frac{f(z)}{(z-a)^{n+1}}dz$$

holds.

Observe that this formula contains the

Cauchy's integral formula if n=0, with 0!=1.

The proof of this is based on the ability to put derivative sign into the integral sign.

Theorem 2: Cauchy's inequality

In the same conditions of the previous theorem, let M be a positive constant such that for all z of the curve C \( |f(z)| \le M \), then it is fulfilled

$$|f^{n}(a)| \le \frac{M n!}{r^{n}}$$

The following theorem due to Liouville states that there not exists a bounded and

holomorphic function in the whole complex plane except if it is constant:

Theorem 3: Liouville's Theorem

If f is

holomorphic in the whole plane \( \mathbb{C} \) and f is bounded, that is \( |f(z)| \le M \forall z \in \mathbb{C}\) then f is constant.

The proof of Liouville's theorem is direct from Theorem 2 by taking increasingly larger radious.

Theorem 4: Fundamental theorem of Algebra

Let's \( P(z) = a_{0} + a_{1}x + ... + a_{n}x^{n} \) be a polynomial with complex coefficients of degree greater or equal than 1. Then P(z) has at least one root in \( \mathbb{C} \).

Note that it actually has roots because\( z_{0} \) is a root of P, then

\( P(z) = (z-z_{0})( b_{0} + b_{1}x + ... + b_{n-1}x^{n-1}) = (z-z_{0}) Q(z)\).

Thus, Theorem 4 can be applied to Q(z). Operating by induction it is fulfilled that P(z) has complex roots.

To prove Theorem 4, it is enough to consider:

\( f(z) = \frac{1}{P(z)} \).

If P(z) has not any root in \( \mathbb{C} \) then f(z) is

holomorphic in the whole plane \( \mathbb{C} \), also f is bounded,

by Liuoville's theorem f is constant, so P(z) would be constant which contradicts the hypothesis.

Theorem 5: Principle of the maximum module

If f

holomorphic on and into a region bounded by closed path C. Then the maximum of | f | occurs over C.

Note: the same can be applied to the minimum.

Theorem 6: Medium Value theorem of Gauss

In the same conditions as

Cauchy's integral formula, it is fulfilled

\( f(a) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2 \pi} f(a+re^{i\theta}) d\theta\)

The proof of this fact is easy, it is enough to observe that in the

Cauchy's integral formula we can parametrize C as

\(|z-a| = r \Rightarrow z= a + re^{i\theta} \).

Then

Cauchy's integral formula becomes

\( f(a)= \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{0}^{2 \pi} \frac {f(a+re^{i\theta}) ir e^{i\theta} }{r e^{i\theta}} d\theta = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2 \pi} f(a+re^{i\theta}) d\theta\)

What is what we wanted to proof.