Most of the complex variable functions are extensions of the real variable functions. For instance

the complex logarithm,

wich calculation is realized in the following way

$$log z = log|z| + i Arg\,(z), \, Arg\,(z) = arg(z) + 2k\pi i$$

It is an extension of its homologous logarithm from the real variable. Now we can calculate logarithms of negative numbers and other complex numbers in general.

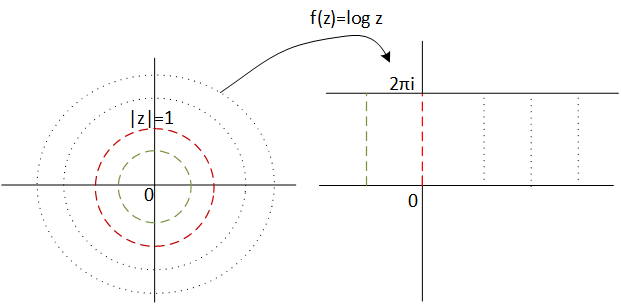

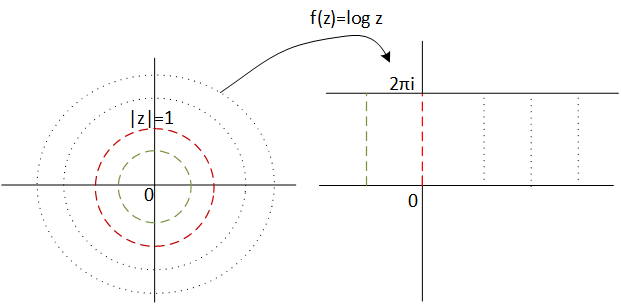

Because we can not visualize the graph of one complex variable functions as in the real case, it is interesting to see how certains regions

of the plane are transformed through our function. In our example of

the complex logarithm,

we will procced to see how the unit circumference is transformed through it, this we take the set

$${z\in \mathbb{C} : |z|=1}$$

We know that it image through logarithm will be contained into imaginary axis since

$${Re(log(z)) = 0 \,\,, \forall z \in \mathbb{C} : |z|=1}$$

In addition, we also know that it will be contained in the interval \([0,2\pi]\) from imaginary axis because

$${Im(log(z)) \in [0, 2\pi] 0 \,\,, \forall z \in \mathbb{C} : |z|=1}$$

Thus the unit circumference is transformed into the segment \([0,2\pi]\) of imaginary axis.

Therefore, it is easy to see from here that any circumference of radius r is transformed into a segment \(log(r)\,x \,[0,2\pi]\).

And from this we deduce that the whole complex plane becomes the band given by the whole set

$${z\in \mathbb{C} : Im(z) \in [0, 2\pi]}$$

Observe that negative part of the band is the image of the interior of the circumference of radius one and the positive part is the image of the exterior, let take a look the following figure:

Figure 1: Image of complex plane \( \mathbb{C} \) through function f(z) = log z.

Easy. Do not? This is the idea: we can not render complex variable function graphs but what we can do is see the geometry of its transformation through some pre-known sets.

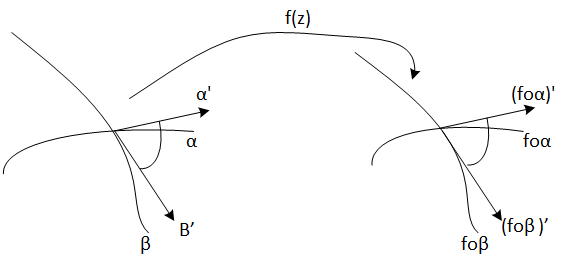

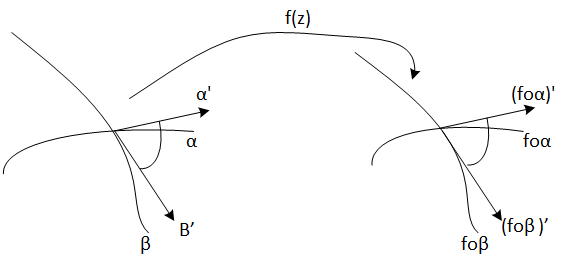

A map is said to be conformal when it keeps the angles, that is, f is a conformal map to z if given two regular curves

$$\alpha: [a,b]\rightarrow \mathbb{C} $$

$$\beta: [c,d]\rightarrow \mathbb{C} $$

Then

$$\frac{\alpha'(z)}{\beta'(z)} = \frac{(f\circ \alpha)'(z)}{(f\circ \beta)'(z)}$$

Given two curves that cross at a certain point z, the angle at which the tangent vectors of curves intersect is kept by the map f.

Figurae 2: Angle conservation by a conformal map.

Note that in order to above definition to be fulfilled, it must be fulfilled in particular that \(f'(z) \neq 0 \).

If function is

holomorphic (ie, it has complex derivate), then there is an interesting theorem called

Map conformal Theorem

Lets the complex function

$$ f: U \subset \mathbb{C} \mapsto \mathbb{C} $$

f is a conformal map if and only if f is also an

holomorphic function and \(f'(z) \neq 0 ,\,\,\forall z \in U \)

For instance in the complex plane the family of lines Imz = cte and the family of vertical lines Re (z) = cte, are orthogonal.

Theorem of map conformal applied here will guarantees that the image of such families by a

holomorphic function,

are orthogonal curve families as well.

It is interesting to note also that any

holomorphic function

f(z)=w maps "shorts distances" in the plane z into "shorts distances" in the w plane. The factor of increase or decrease distances is given por |f'(z)|.

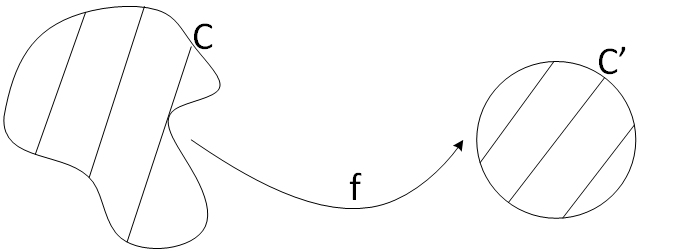

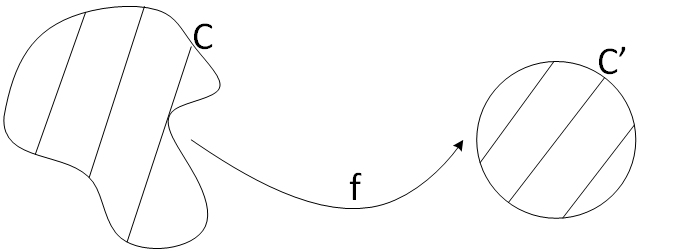

The following theorem guarantees that given every simply connected region can be transformed, through an

holomorphic function

into the unit disk.

Theorem of Riemann map

Let C be a closed and simple curve that is the border of a region R. Let now C' be

the unit circumference that makes up the border of a region R ' formed by D((0,0), 1), ie the disk with center 0 and radius 1.

Then there exists a f

holomorphic

and byective function from R into R', in adittion:

$$ \forall w \in C' \, \exists \, z \in C : w= F(z) $$

Figure 3: Riemman map theorem.

In particular, any region with "worthy" properties, that is, simply connected and limited by a closed and simple curve, (therefore bounded)

can be applied into unit disk through any

holomorphic function.

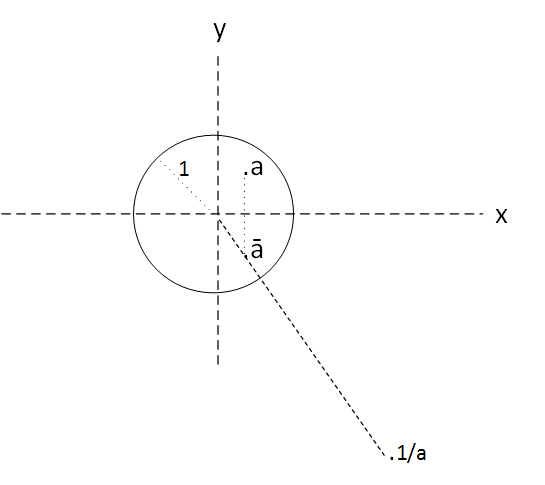

Example

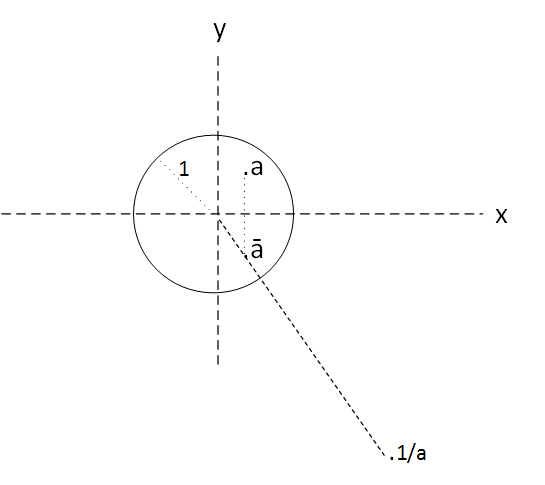

\(f(z)=\frac{1}{z} \)

It is easy to see that f "puts the inside of the unit disk" to the outside of the unit disk and, conversely, what is outside of the disk "puts it" inside the disk.

It is not so easy to see that actually, f is not an inversion: each point z of the interior of the disk does not assign an exterior w such that argument of w = argument of z and radius of w = inverse of the radius of z .

That is, it is not true that

\(arg \frac{1}{z} = arg z \)

Because definition of

complex conjugate,

f first gets the complex conjugate of z and then yes, obtains the w in the same radius. So it is true

\(arg \frac{1}{z} = arg \bar z \)

Figure 4: function \(f(z) = \frac{1}{z}\)

Example

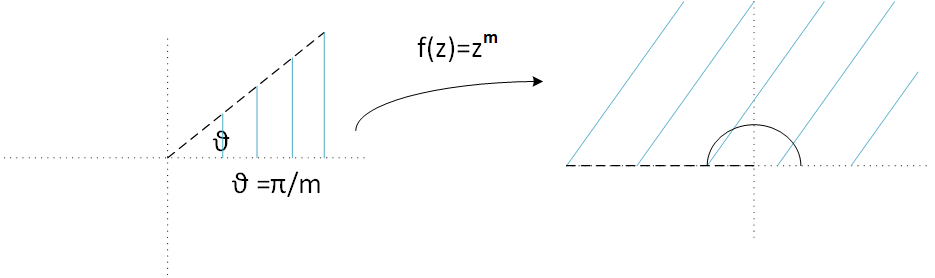

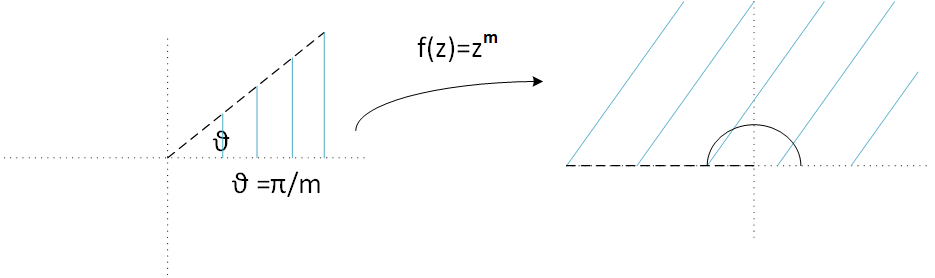

\(f(z)= z^{m}\)

Figure 5: function \(f(z) = z^{m}\)

In this case function f transforms a sector of the plane with angle \( \frac{\theta}{m} \) to the superior semiplane.

This is because

power complex transformation,

whose expression es

$$z^{m} = |z|^{m} e^{(mi\theta +2mk\pi i)} $$.

Note that to calculate power m of a complex number it argument is multiplied by m and it module is powered m too.